Sugars and dextrins: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

| Dextrins || <center>+</center> || Non-fermentable | | Dextrins || <center>+</center> || Non-fermentable | ||

|} | |} | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 02:26, 19 December 2020

Please check back later for additional changes

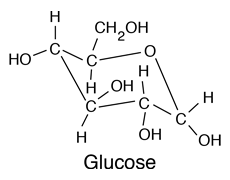

Sugar, a type of carbohydrate, is a core ingredient of any fermented beverage because it is the source of carbon used by yeast to grow and produce alcohol plus carbon dioxide. A basic unit of sugar is called a monosaccharide; it is a small molecule containing a hexagonal "ring" structure. There are several types of monosaccharides, such as glucose. In plants (such as barley, grapes, etc.), these sugar units are often bound together in lengths ranging from 2 units to chains of many thousands of units. A molecule of 2 bound sugar units is called a disaccharide and 3 bound sugar units is a trisaccharide. Longer chains of sugar units are generally called oligosaccharides or dextrins, but very long chains (e.g. starch molecules) are not considered sugars.

This article discusses the naturally-present sugars in beer. To learn about added sugars, see Adjuncts.

Sugars in wort and beer

For the production of beer, malted grain is typically a primary ingredient because of its high starch content combined with the natural presence of starch-degrading enzymes. The starch is made up of units of glucose and it undergoes a degradation process called saccharification during mashing, which produces an array of different configurations of sugars made from the glucose units. Some of these sugars are utilized by the yeast during fermentation, while others are generally unable to be utilized, and instead they contribute directly to the sensory characteristics of the beer.[1][2] Barley also contains a small amount of sucrose.

Sugars created during mashing:

- Glucose (also known as dextrose) is a monosaccharide. Glucose is very easily fermented. High levels of glucose in wort can increase ester formation during fermentation.

- Fructose is a monosaccharide present in small amounts due to the breakdown of sucrose. Fructose is very easily fermented.

- Sucrose (also known as saccharose) is a disaccharide, glucose bound to fructose. Sucrose is partially degraded during mashing, and the yeast quickly complete the degradation during fermentation. Therefore sucrose is very easily fermented.

- Maltose is a disaccharide, two glucose units bound together. This is normally the most abundant sugar in wort. Generally, maltose is easily fermented. A high maltose level in wort enhances fermentation speed and attenuation. Caveat: a special type of maltose called isomaltose contains an α-1,6 bond, and it is only partially fermented.[3]

- Maltotriose it a trisaccharide, a chain of three glucose units bound together. Most "brewers yeast" can ferment maltotriose. It is generally not utilized until after all of the maltose has been fermented, and in many cases a portion of the maltotriose remains unfermented.[4][3] In other words, maltotriose is difficult to ferment and its utilization may be incomplete.

- Dextrins (also known as oligosaccharides) are chains of 4+ glucose units, typically with one or more branches. These are generally not fermented (except by certain yeast strains), and they carry through to the finished beer.[3] Branched dextrins are beneficial because they contribute to the body and mouthfeel of the finished beer, but excessive levels will result in a poorly attenuated product.[5][6][7][1]

Summary[4]

| Sugars | Presence | Fermentability |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose, fructose, sucrose | Very high | |

| Maltose | High | |

| Maltotriose | Low | |

| Dextrins | Non-fermentable |

See also

References

- ↑ a b Holbrook CJ. Brewhouse operations. In: Smart C, ed. The Craft Brewing Handbook. Woodhead Publishing; 2019.

- ↑ Fox GP. Starch in brewing applications. In: Sjöö M, Nilsson L, eds. Starch in Food. 2nd ed. Woodhead Publishing; 2017:633–659.

- ↑ a b c Guerra NP, Torrado-Agrasar A, López-Macías C, et al. Use of Amylolytic Enzymes in Brewing. In: Preedy VR, ed. Beer in Health and Disease Prevention. Academic Press; 2009:113–126.

- ↑ a b Kunze, Wolfgang. "3.2 Mashing." Technology Brewing & Malting. Edited by Olaf Hendel, 6th English Edition ed., VBL Berlin, 2019. pp. 219-265.

- ↑ MacGregor AW, Bazin SL, Macri LJ, Babb JC. Modelling the contribution of alpha-amylase, beta-amylase and limit dextrinase to starch degradation during mashing. J Cereal Sci. 1999;29(2):161–169.

- ↑ Evans DE, Fox GP. Comparison of diastatic power enzyme release and persistence during modified Institute of Brewing 65°C and Congress programmed mashes. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 2017;75(4):302–311.

- ↑ Evans DE, Li C, Eglinton JK. The properties and genetics of barley malt starch degrading enzymes. In: Zhang G, Li C, eds. Genetics and Improvement of Barley Malt Quality. New York: Zhejiang University Press, Hangzhou and Springer Verlag; 2009:143–189.