Sugars and dextrins

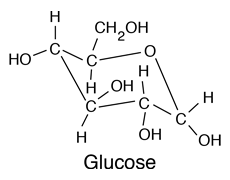

Sugar, a type of carbohydrate, is a core ingredient of any fermented beverage because it is the source of carbon used by yeast to grow and produce alcohol plus carbon dioxide. A basic unit of sugar is called a monosaccharide; it is a small molecule containing a hexagonal "ring" structure. There are several types of monosaccharides, such as glucose. In plants (such as barley, grapes, etc.), these sugar units are often bound together in chains ranging from 2 units to many thousands of units long. A molecule of 2 bound sugar units is called a disaccharide and 3 bound sugar units is a trisaccharide. Longer chains of sugar units are generally called oligosaccharides or dextrins, but very long chains (polysaccharides such as starch molecules) are not considered sugars.

This article discusses the naturally-present sugars in beer. To learn about added sugars, see Adjuncts.

Sugars in wort and beer[edit]

For the production of beer, malted grain is typically a primary ingredient because of its high starch content combined with the natural presence of starch-degrading enzymes. Starch is made up of units of glucose. During mashing, the starch undergoes a degradation process called saccharification, which produces an array of sugar configurations made from the glucose units. Some of these sugars are utilized by the yeast during fermentation, while others are generally unable to be utilized, and instead they contribute directly to the sensory characteristics of the beer.[1][2] Barley also contains a small amount of sucrose.[3]

Sugars created during mashing:

- Glucose (also known as dextrose) is a monosaccharide. Glucose is very easily fermented. High levels of glucose in wort can increase ester formation during fermentation.

- Fructose is a monosaccharide present in small amounts due to the breakdown of sucrose. Fructose is very easily fermented.

- Sucrose (also known as saccharose) is a disaccharide, glucose bound to fructose. Sucrose is partially degraded during mashing, and the yeast quickly complete the degradation during fermentation. Therefore sucrose is very easily fermented.

- Maltose is a disaccharide, two glucose units bound together. This is normally the most abundant sugar in wort. Generally, maltose is easily fermented. A high maltose level in wort enhances fermentation speed and attenuation. Caveat: a special type of maltose called isomaltose contains an α-1,6 bond, and it is only partially fermented.[4]

- Maltotriose is a trisaccharide, a chain of three glucose units bound together. Most "brewers yeast" can ferment maltotriose. It is generally not utilized until after all of the maltose has been fermented, and in many cases a portion of the maltotriose remains unfermented.[5][4] In other words, maltotriose is difficult to ferment and its utilization may be incomplete.

- Dextrins (also known as oligosaccharides) are chains of 4+ glucose units, typically with one or more branches. A more specific group called "limit dextrins" are branched dextrins small enough that they can no longer be degraded by α-amylase or β-amylase. Dextrins are generally not fermented (except by certain yeast strains), and they carry through to the finished beer.[4] They are beneficial because they contribute to the body and mouthfeel of the finished beer, but excessive levels will result in a poorly-attenuated product.[6][7][8][1] Variation in the size distribution of limit-dextrins also directly impacts beer flavor.[9]

Summary of sugars present in wort:[5]

| Sugars | Presence | Fermentability |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose, fructose, and sucrose | Very high | |

| Maltose | High | |

| Maltotriose | Medium to low | |

| Dextrins | Non-fermentable |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ a b Holbrook CJ. Brewhouse operations. In: Smart C, ed. The Craft Brewing Handbook. Woodhead Publishing; 2019.

- ↑ Fox GP. Starch in brewing applications. In: Sjöö M, Nilsson L, eds. Starch in Food. 2nd ed. Woodhead Publishing; 2017:633–659.

- ↑ Fox GP, Staunton M, Agnew E, D'Arcy B. Effect of varying starch properties and mashing conditions on wort sugar profiles. J Inst Brew. 2019;125(4):412–421.

- ↑ a b c Guerra NP, Torrado-Agrasar A, López-Macías C, et al. Use of Amylolytic Enzymes in Brewing. In: Preedy VR, ed. Beer in Health and Disease Prevention. Academic Press; 2009:113–126.

- ↑ a b Kunze W, Hendel O, eds. Technology Brewing & Malting. 6th ed. VBL Berlin; 2019:219–265.

- ↑ MacGregor AW, Bazin SL, Macri LJ, Babb JC. Modelling the contribution of alpha-amylase, beta-amylase and limit dextrinase to starch degradation during mashing. J Cereal Sci. 1999;29(2):161–169.

- ↑ Evans DE, Fox GP. Comparison of diastatic power enzyme release and persistence during modified Institute of Brewing 65°C and Congress programmed mashes. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 2017;75(4):302–311.

- ↑ Evans DE, Li C, Eglinton JK. The properties and genetics of barley malt starch degrading enzymes. In: Zhang G, Li C, eds. Genetics and Improvement of Barley Malt Quality. Springer; 2010:143–189.

- ↑ Yu W, Zhai H, Xia G, et al. Starch fine molecular structures as a significant controller of the malting, mashing, and fermentation performance during beer production. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;105:296–307.